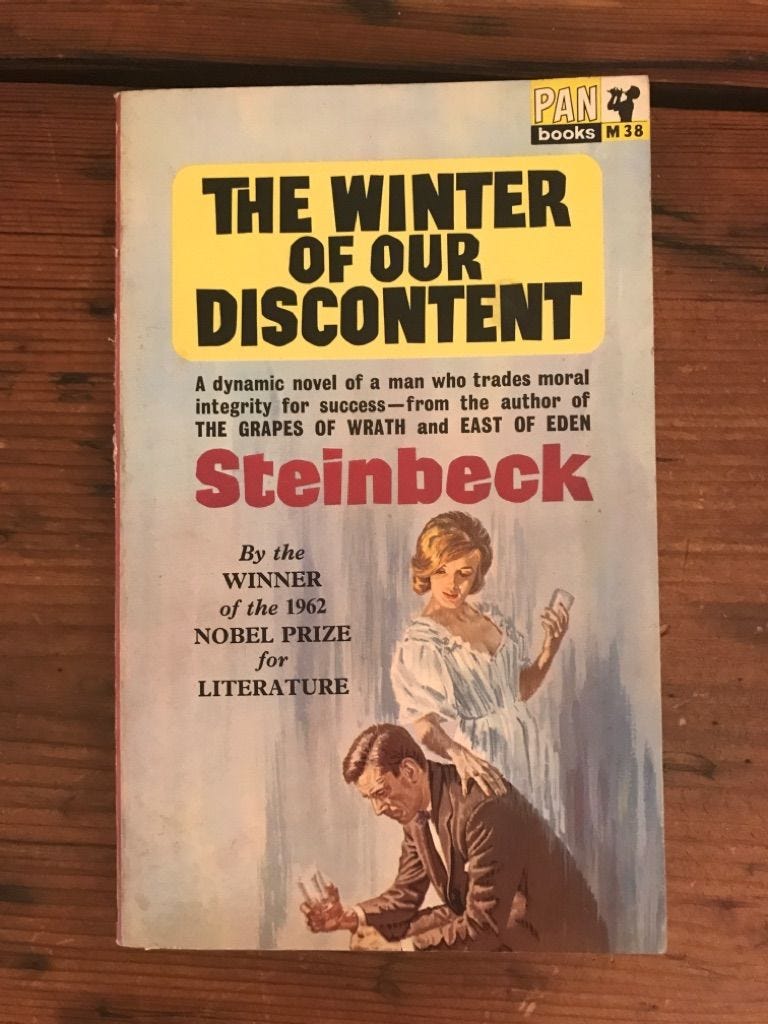

The Winter of Our Discontent

And why I read this novel 5 times

I remember the first time I read John Steinbeck's The Winter of Our Discontent. I was in my early twenties and had finished reading his Grapes of Wrath, The Pearl and Tortilla Flats in a row. I was moved to bits with his intimacy of sight and his compassion for people who the world viewed as failures, but for the writer were real survivors and heroes. The backgrounds of all the novels was earthy, and his power of writing made me see the dirt deep inside the nails of his hardy protagonists. These were moving dioramas of people who refused to give up.

And then I picked up this book. And the way it's background unravelled - urbane, full of sunshine, following the fortunes of a family, set in a small town in the eastern coastline of USA - it could have been written by a different writer. Until it reached into it's dark core and it's shattering dilemmas. It's darkness was greater than the black destinies of all the characters of all the books which came before this.

The universality of the ethical dilemmas of it's protagonists made me revisit this book again and again. It was almost as if I grew up reading this book - or maybe the book grew into me. And every time I struggled with it's issues, and each time I reacted to it's themes differently. It was almost as if my evolution as a person was charted out in my different readings of the same book. I just finished my fifth reading of the book. And I sit back, as moved and disturbed as ever, with its problems and struggles and heartbreaking resolutions.

The year is 1960. Ethan is a clerk in a store, which at one time his ancestors owned. He has a wife, a son, a daughter. And society is at the cusp of a materialistic explosion, and its effect is making inroads into every home. Ethan represents a lineage which is one of the richest in the town, but today he doesn't even have money to have a television or take his family for a holiday. And every time he enters his home, he enters a vortex of his family's desires and ambitions. And finally he is forced to make choices which burst into smithereens every value, every ethic he thought were his own.

The theme is so contemporary and universal, that it seems it's written for today. At a time when our society has sharper economic divisions but similar explosions of expectations for a good life, what does a person do to fulfill desires? And particularly when he sees the corrupt becoming rich beyond any limit, with no holds barred - and becoming respectable to boot.

Ethan at one point says -

"Now a slow, deliberate encirclement was moving on New Baytown, and it was set in motion by honorable men. If it succeeded, they would be thought not crooked but clever. And if a factor they had overlooked moved in, would that be immoral or dishonorable? I think that would depend on whether or not it was successful. To most of the world success is never bad. I remember how, when Hitler moved unchecked and triumphant, many honorable men sought and found virtues in him. And Mussolini made the trains run on time, and Vichy collaborated for the good of France, and whatever else Stalin was, he was strong. Strength and success— they are above morality, above criticism. It seems, then, that it is not what you do, but how you do it and what you call it. Is there a check in men, deep in them, that stops or punishes? There doesn’t seem to be. The only punishment is for failure. In effect no crime is committed unless a criminal is caught."

But what do small people do with the small defeats of their daily life? What do WE do with the choices we are given ever so often between keeping a moral high ground & despair and compromised morality & instant gratification? The book is littered with the angst of ethical choices and the trauma of living below the expectation-levels of those who mean the most to you.

The happy irony of this book is that even as it unravels it's onerous ethical knots, it's writing is bright, funny and sparkling. And like the best of writing, it works incredibly on numerous levels. It delineates married life and love within it's paradoxes: how often, how little we know the people we love the most, as also how our love doesn't lessen in spite of it. How both the villainy of circumstances and the heroism of choices both reside within us. And, more shatteringly, how our fragilities, foibles and fables find their way into our children - until they openly mirror our true selves, and we are helpless to do anything.

Packed with memorable characters and a storyline throbbing with inner tension, this is ultimately a book about defeat and redemption - and how destiny is just a handmaiden of the determinism of our choices. And why, in the darkest nights of our life we cannot let the light of our lives to go out.

Trivia:

This book was specifically mentioned in the citation of Nobel Prize awarded to Steinbeck. The irony was that this book was savaged critically and hurt Steinbeck so much that this became his last novel. All books after this were non-fiction. Today, of course, this book stands as a literary monument documenting man's ethical dilemmas.

Hear these poems, curated from Uncut Poetry:

The Tragedy of Seeing Life as a Broken Enterprise:

In The Drift We Will Find Our Certainties:

I loved this essay. Thanks so much for such a detailed and sensitive response to Steinbeck's work. I've ordered the book and was so inspired by the quote "I wonder how many people I've looked at all my life and never seen" that it will be the theme of our next calendar at the Latika Roy Foundation (I will send you a copy as a thank you!).