1For me, a city is a feeling. It’s a bit like when you enter a house and something inside you tells you if it’s an happy open-hearted place - or not. The same happens when you experience a city. Let me tell you what I think of cities I know, in metaphorical terms.

Bombay is an open-necked T-shirt, the sun hot and bright on the skin but forever ready for rains; Delhi is a buttoned-down shirt, expensive, but the person wearing it is unwashed; Bangalore is how your skin feels after you make love, sweaty, sensitive to touch, but with a memory of being persuaded into the bedroom; Calcutta is Rose on a raft, terror bristling her skin, surviving a Titanic, kept afloat by Jack (who is symbolic of it’s gorgeous people), but drifting, drifting.

And Lucknow? Let me come to it.

The airport welcomes you with “Muskaraye ki aap Lucknow mein hai.” And I love it that everybody is speaking Hindi. But different versions! Fashionable girls mill around the airport carousel, midriffs showing, speaking in thick Bundelkhandi accents. There’s a happy conviviality, possibly of returning home. I smile to myself, completely charmed. And when I step out, It’s cold but coruscating. And then one runs into the usual Indian city!

Everything is the same - until it is not.

Being a Calcuttan, I know more than anybody else, how much a city’s story makes a difference to its people, even if they are not aware of its details. When you decide to plug your being into a city’s rhythms and heart-stops, you are going into both a celebration of its beauty - and into sharing its (and your) vulnerabilities. A city is yours when it can let you be what you want it to be, even as it asks you to accept its warts as much as it’s beauty spots.

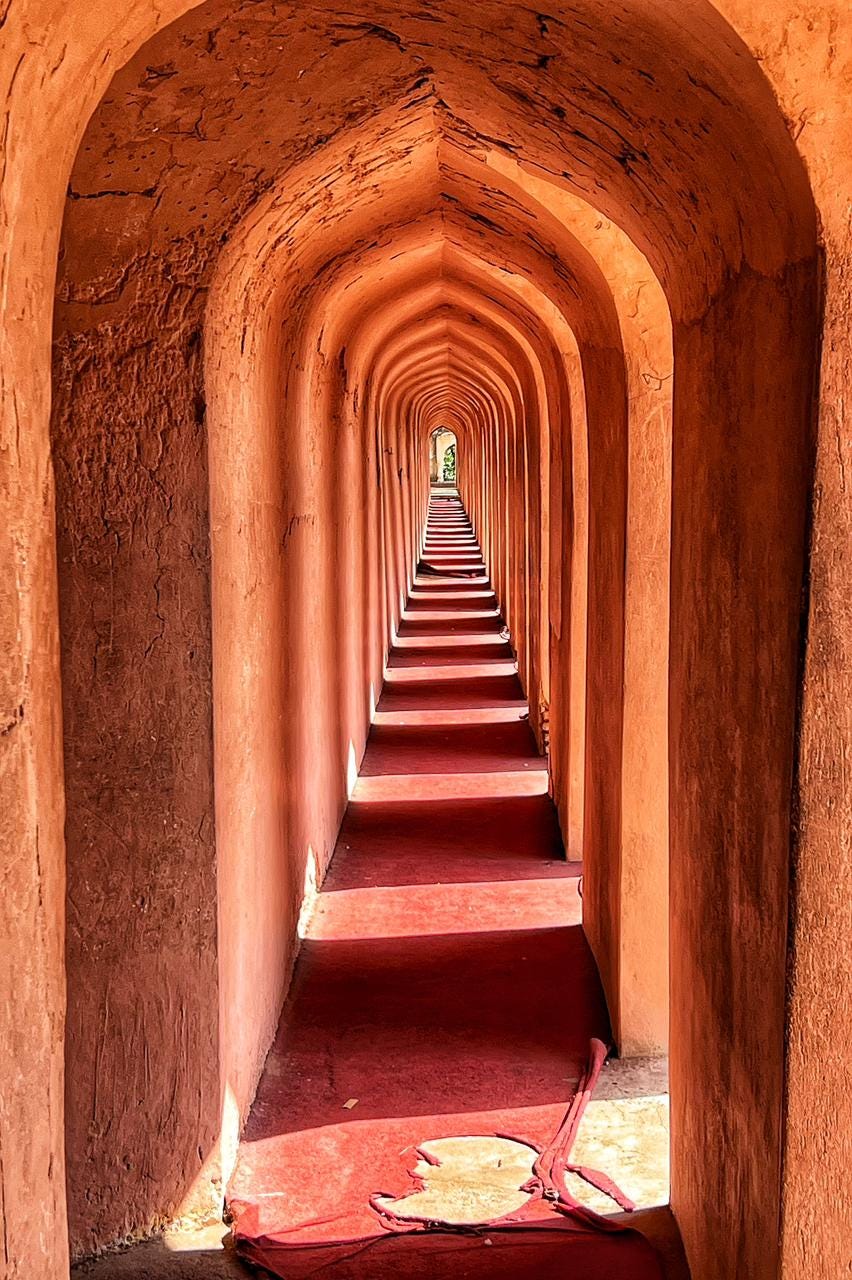

Where do you touch the soul of a city? In the curve of its ancient arches, in its open-faced facades or close-fisted clubs? Is it the tea-seller who is open to conversation or the scholar who will defend the indefensible? Does the glory of past lives have anything to do with the present or the fact that walls lay crumbling in the inner city?

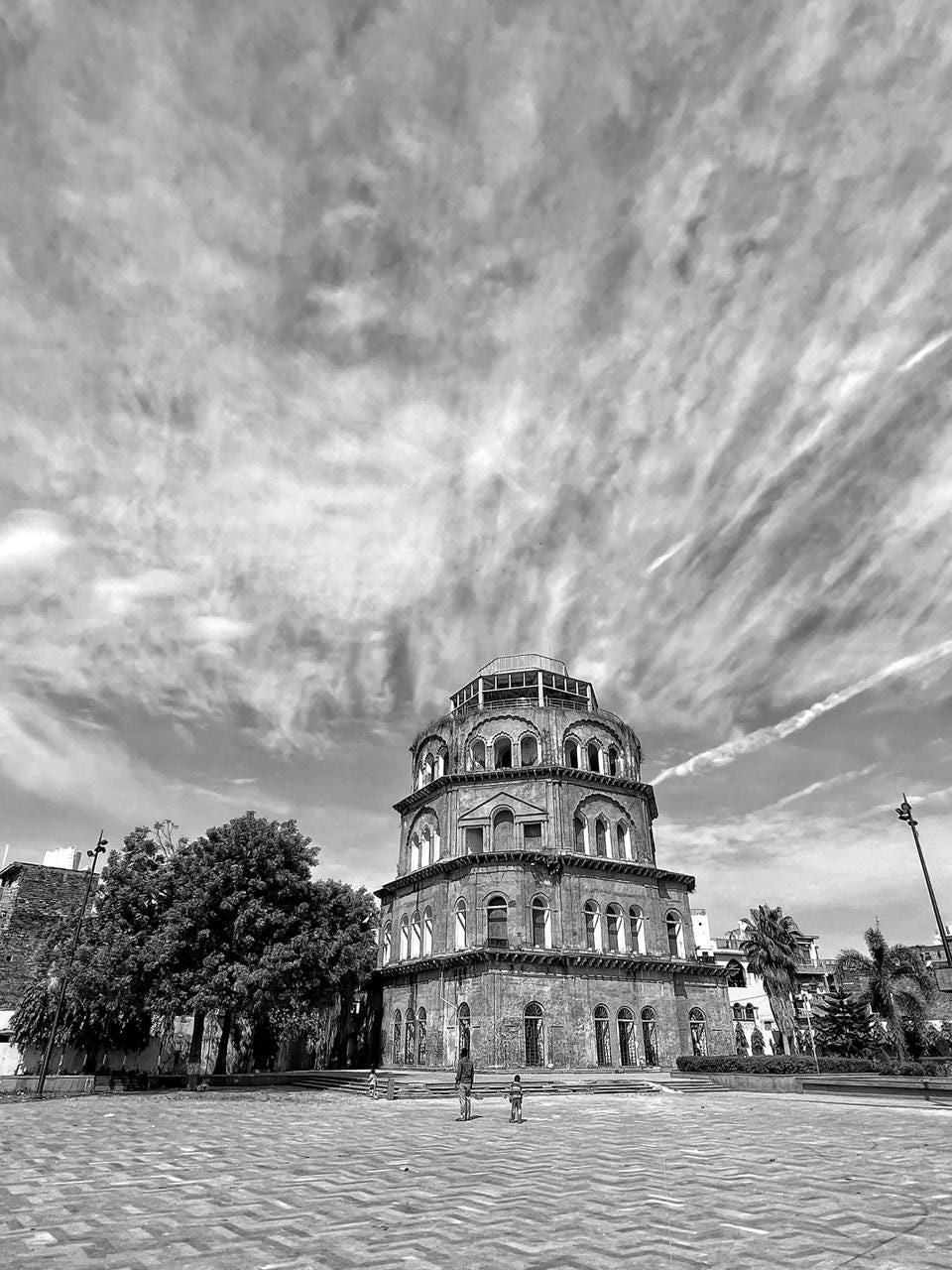

Muzafur, my guide in the Bada Imamdara, talks about the largess of the then Nawab of Awadh, when his kingdom was going hungry, and how he commenced building a monument - breaking in the night what was built in the day, so that people would continue to earn without having to beg. A story like this, when repeated a hundred times every day, must - and will - seep into the consciousness of its denizens.

The demarcation was clearer when I went to The Residency, the 33-acres-spread of ruins which even in their complete destruction showed signs of decadence and luxury - Britishers who’d came to rule the Nawab got him to pay for all of it. Even after all these years, it was a special feeling to see tangible traces of the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny, when the soldiers turned against their British rulers and shelled the place as the Britishers cowered inside basements. The archaeologists have left the bullet-ridden walls and signs of cannonballs intact, possibly as signs of what karmic retribution looks like.

Lucknow then is a paradox. Because it has always lent itself out to potentates. Historically, Lucknow was the capital of the Awadh region, controlled by the Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughal Empire. It was transferred to the Nawabs of Awadh. In 1856, the British East India Company abolished local rule and took complete control of the city along with the rest of Awadh and, in 1857, transferred it to the British Raj. Along with the rest of India, Lucknow became independent from Britain in 1947. *

But much more than subtractions or dismissals, each reign has brought an idiosyncratic flavour to the city - you have to see the Mayawati-created Ambedkar Park to understand the incredulity of what I say. In its concrete awe-inspiring waste is a megalomaniacal vision, executed to perfection, but strangely appropriate as a bridge from a past of indulgence to one of accountability. Because, time and again, in one conversation after another, it’s clear that people are looking ahead, and there’s an impatience to shrug the troubling agendas of a few who held the populace at ransom. Yogi is respected, his iron hand is feared, everybody knows he means business.

As I walked the lanes of Hazratganj, in search of the famous Sharma’s tea stall, I sensed the life and the beauty of appropriations. However bigoted or bewitching a vision of what one wants of the place one adopts, stays in or rules, when one does it from a place of bringing balance, there is bound to be resistance, and then grudging acceptance.

I sat in a leafy park with my khullad chai and mathri, amongst college kids who spoke of a boring professor, a suited guy extolling the benefits of investing in the stock market directly to someone who seemed to be a SIP guy. There were three ladies with shopping bags, happily biting into steaming samosas and simultaneously speaking. Two boys passed by, dressed as mendicants, stopping to ask for alms, as if it was pocket money coming to them as a lark.

This was serenity and happiness in the middle of the day, in the middle of the most populated part of the city. Possibly this is what each city desires to create - and give to its citizenry - a place to stop by, a life to linger in. Simplicity looks so simple. Often it has to be claimed, sometimes in blood, always with a history.

So. Lucknow. It’s the feeling of putting on one’s home slippers, after a long long day.

* the last part is culled from Wikipedia, as I was searching for a summary of the complex history of the city, and this did just fine.

Pass these things forward - love, a lil’ appreciation, your big heart - and this substack :)

All photographs by me