Finding Home in Places We've Left Behind

Revisiting a place where one has one’s roots is tricky business.

On the one hand, there is enough familiarity - relatives, school chums as unrecognisable adults, hazy lines of playgrounds, peacocks, changing views from rooftops, familiar cracks now deeper - and on the other, one enters the familiar as a complete stranger. The air is lighter, the light is sharper, the language is alien in spite of familiar intonations, and one sits on judgement. And a sense of superiority emerges - as if the place I’ve settled in is not only different, but also way ‘ahead’, whatever the meaning of that word is.

But the bigger tragedy is how we look at what was hometown, nay home, is now a place to judge, to compare, to find it falling short.

We move on in life - whether it indicates moving forward is a moot point. What does linger is what we leave behind. Sometimes as a place stuck in a time-wrap, sometimes merely reluctant to find new beats, happy in its anachronisms. Sometimes as people, who are happy to remain what they are, tiny dreams ensconced in comfortable immobility. And that is a choice to be happy in one’s own quiddities, within one’s particularities.

And who are we to judge, just because we have found different dreams, racier trajectories, more informed choices. If finally what we as human beings seek is serenity and fulfilment, how do we even know whether that is there in the places and people we have left behind?

In our desire to know ourselves better, it is often a good idea to haul ourselves back to our roots, and then just sit back and see ourselves implode, explode, sink or float. If nothing else, we will get to know ourselves better.

The poem

Everything is solid but abandoned.

The sand is hard like burnished steel,

and trees are like overgrown cacti, splaying

out their arms in a silent scream for help.

Dhundlod Public School says the signboard,

an anomaly for a building which should have

paan-chewing clerks of a government building,

instead spewing out children like a sand-storm.

And for a while the road has the scattered rain of screams and chatter.

Tolasoria Skills School waits patiently

for its future clientele. I ask the tea seller -

what does development mean here?

He guffaws, spits into the open drain,

and says we’ve done nothing for centuries

and have survived. Right behind him

is an unused well, four pillars guarding

it’s toothless mouth, with patches

of blue and red, and cracks revealing

the earthen pots packed tightly inside,

shyly peeping out into the world,

a bride revealed to have a torn ghagra.

This place makes me feel guilty

of being well fed in a city where everything

proclaims it has meaning. Here even the chatri

a resting place for travellers is abandoned,

too broken for even the drunkard of the town

or lovers seeking trysts on clean floors.

I talk to my partner of forgotten places,

and she asks when were they remembered?

We walk back to the haveli, our heads down,

as the mist rains on us like a silent torrent,

till we were grinning wryly, cold, wet.

I’ve left this town to its devices,

though it has my blood, sweat, semen,

for a city which now has all the contours of a home,

and has shaped my memory in inflexible ways.

I mused if places have memories

and a sense of being left adrift, and the feeling

I got of being watched by my school, college

was my guilt or a hurt town’s silent reproach?

I will go to the roof in the morning and pour tea

beside turrets now black with a century of grime,

and see the sun catch the plume of a peacock,

walking gingerly in the fallow fields.

There would be smoke from the huts and

women bringing out mattresses out in the sun.

I would know that nothing dies just because I’ve forgotten,

and though some maps might not have names

of places, they do survive.

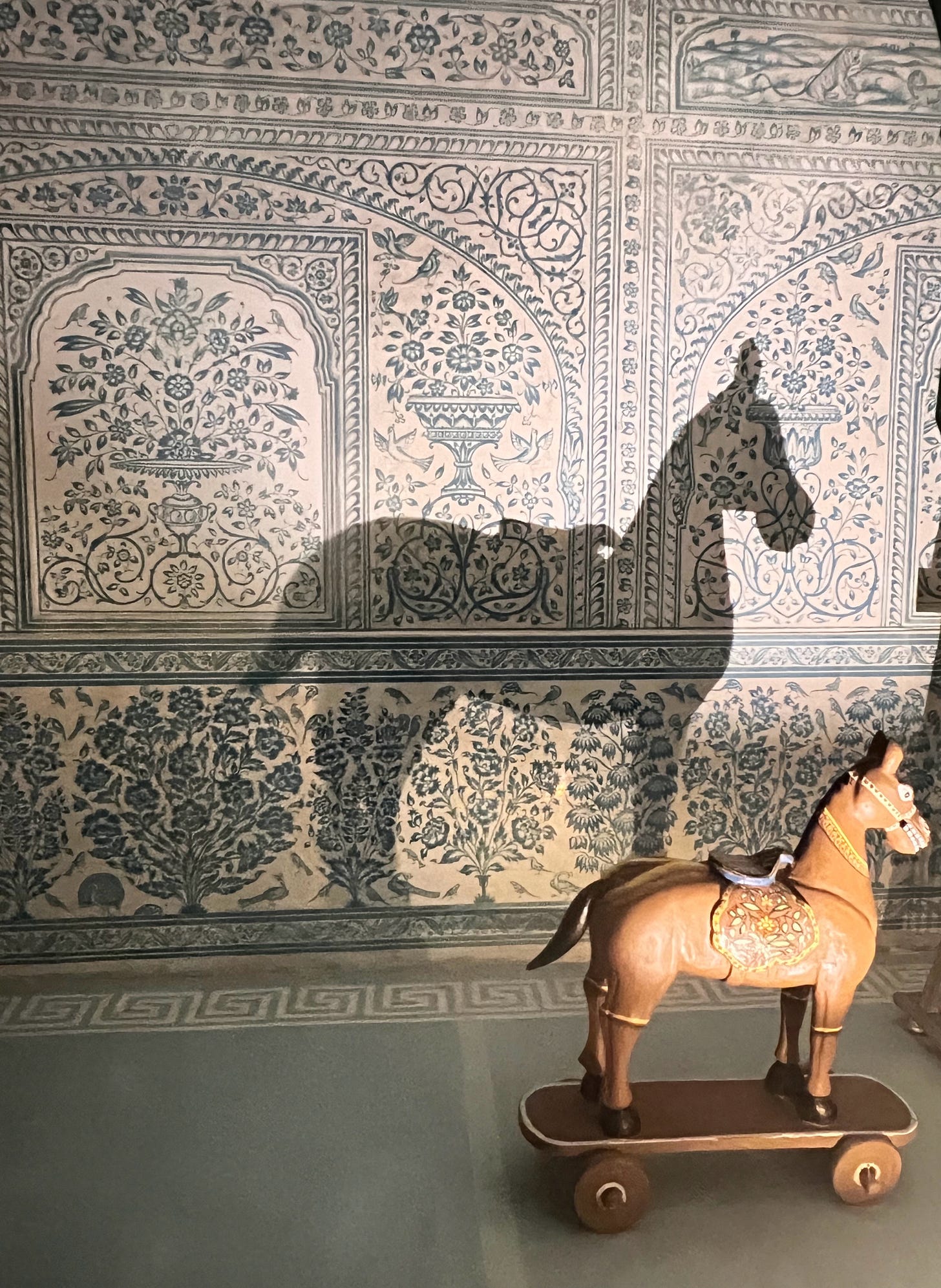

*All photographs clicked by me

I write, so you can enjoy and expand your world. Would you like to support me? Well, here’s what you can do -

share this post -

tell me of your thoughts -

subscribe, if you love it -